Learning to Face Your Opponent

Sometimes, in life, a single word or a single sentence can make a huge difference -- an unexpected communication that penetrates to the core of your being and then radiates from the inside out for the rest of your life. I had one such moment 35 years ago when I was a novice Aikido student in Los Angeles.

Here's what happened: In the dojo, while practicing a new technique with my partner, my teacher walks over to me, observes briefly, looks at me, and utters these eight words: "You have to learn to face your opponent."

I had no idea what she was talking about and just looked at her blankly. Then she stepped forward and gently rearranged the way I was standing, noting that I was standing a bit too obliquely from my partner -- a posture I had taken that was eventually going to require me to OVERCOMPENSATE in order to complete the move, an action that had the potential, she explained, to injure my partner and myself due to all of the unnecessary twisting and turning likely to happen.

In other words, the way in which I had positioned myself in relationship to my partner was off. I was not facing my partner head on. I was being too indirect, about 10 degrees "off to the side" and it was this indirectness, my teacher explained, that had the potential to cause injury. Whoa!

As I let her words sink in, I knew exactly what she was talking about. The wisdom embedded in her eight words cut to the core of my being. What she observed in me at that moment was a very penetrating expression of how I had been living my life -- especially my relationships. Somehow, I was a little bit off... too indirect.. a little out of whack.. skewed to the side. In other words, I wasn't really engaging others as directly as I needed to and it was my indirectness that was contributing to a whole bunch of negative consequences -- some very subtle -- that I had to deal with.

This is one of the amazing things about Aikido or any inner practice that a person commits to. You get to see where you are at and where you are not at. The feedback is immediate. It's humbling. It's confronting. And it's not always easy to take in. But if you are open to the moment and willing to learn from it, much lifelong wisdom can be gleaned.

I am still imbibing this teaching from 35 years ago delivered to me in less than 20 seconds. I am still learning how to be in right relationship to the people in my life -- not oblique... not indirect... not off to one side, and, at the same time not in their face. In Aikido, there is a word for this -- "Hanmi" -- the stance one takes in relationship to the "other."

With whom, in your life, might you need to adjust your stance? Who are you being too indirect with? Who might you be crowding? Who do you need to face? And what, if anything, can you do this week to take the healthiest stance you can take -- so both of you can practice and no one gets injured in the process?

MitchDitkoff.com

Storytelling at Work

Posted by Mitch Ditkoff at 12:30 PM | Comments (1)

September 23, 2021Storytelling and Islam

You have wisdom to share

Ten reasons why people don't share their stories

Why kind of stories do YOU want to tell?

Storytelling for the Revolution

Posted by Mitch Ditkoff at 07:59 AM | Comments (0)

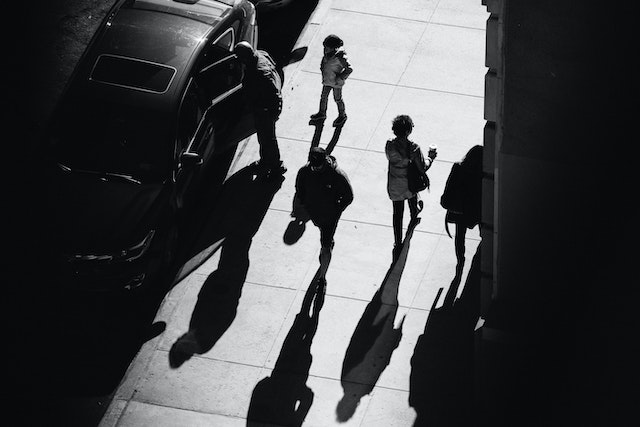

September 08, 2021LIFE IS FULL OF SURPRISES

Thirty two years ago I was walking on a street in midtown Manhattan with a friend of mine when I noticed a man, in a tuxedo, laying face down on the sidewalk. People, in both directions, nicely dressed, were walking by him. No one stopped. As I got closer, I could see that this man was Japanese, in a tuxedo, and bleeding from the forehead. As I bent to get a better look, I could smell the alcohol on his breath. Lots of it. Had he been mugged? I didn't know. But clearly, this bleeding man in a tuxedo was very drunk, in shock, and now beginning to moan.

"Call 911!", I yelled to my friend, trying my best to keep him calm, not wanting his bleeding to get any worse. The only thing I could think of, maybe from a movie I had seen years ago, was to keep him calm. So, I put my right hand on his shoulder, gently squeezed, and started telling him over and over again that "everything was going to be alright and help was on the way."

Nothing I did or said made a difference -- either because he was drunk, in shock, or didn't understand a single word of English. The more I spoke, the more he tried to wiggle away from me to the building just a few feet to our right -- trying, it seemed, to get the support he needed to stand. This, I knew, was a terrible idea as it would only quicken his bleeding. And so I kept on telling him, again and again, that everything was going to be alright and help was on its way.

But no matter what I said or how I said it, he kept making his way across the sidewalk to the marble facade on the building just a few feet away. And then, having moved beyond all my attempts to keep him still, he leaned against the wall and, wobbling, did his best to stand.

When this Japanese man in a tuxedo with a gash on his forehead stood to his full height, he immediately began to fall forward. That's when I reached out, in Good Samaritan mode, spread both of my arms wide and attempted to break his fall. And that's when he punched me in the face. I never saw it coming. BAM! A classic roundhouse. A sucker punch. My glasses went flying, both of my lenses popping out, me now bleeding from the bridge of my nose -- as the ambulance, sirens screaming, came screeching up to the curb, three paramedics jumping out and wrestling him to the ground, putting him in a straight jacket, then onto a stretcher and into the back of the ambulance, sirens screaming again as it drove away.

Crawling on my hands and knees, squinting and bleeding, I found both of my lenses and my frames, now very bent. Then I stood slowly, took the hand of my friend, and both of us, in silence, continued on our way.

More stories here

Photo: Dominik Leiner, Unsplash

Posted by Mitch Ditkoff at 12:39 PM | Comments (0)

September 07, 2021You Are a Universe of Stories

Astronomers, in 1996, attempted a very interesting experiment. They pointed the most powerful telescope in the world, the Hubble space telescope, into a part of the sky that seemed to be completely empty, a patch of the universe long assumed to be devoid of even single planet or star. This experiment was a somewhat risky one, since time on the Hubble telescope was quite expensive and in very high demand. Indeed, there were many highly respected scientists, at the time, who questioned whether "looking at nothing" was a wise use of time and resources. Nevertheless, the experiment proceeded.

When the lens of the telescope was finally closed, 10 days later, and the images from deep space were processed, more than 3,000 galaxies had been detected, each galaxy containing hundreds of billions of stars.

Eight years later, in 2004, astronomers decided to perform the experiment again, this time pointing the Hubble telescope towards a different patch of sky -- a section of the universe also assumed to be completely empty.

At the end of this second experiment, using advanced detectors and filters that allowed more light through than ever before, 10,000 new galaxies were discovered -- each one also containing billions of stars.

As a writer and storyteller, I have asked many people to tell me their stories -- moments of truth in their life... or rites of passage.. or just something interesting that happened to them. Not infrequently, the people I ask look back at me with a blank stare, explaining, in various ways, that they really don't have any stories to share -- that not all that much interesting has happened to them in their life.

Metaphorically speaking, I am directing their attention to a patch of their own night sky and what I hear back from them is that there is nothing there. To them, it is empty.

As a long-time researcher into the storytelling phenomenon, I know their conclusion is not even remotely close to being true. Each and everyone of us, no matter where we were born or what our life experiences have been, contain a universe of stories within us: Memorable happenings... moments of truth... rites of passages... unforgettable encounters... lessons learned... cool experiences ... and a whole bunch of off the grid moments -- small, medium, and large.

And yet, when we are asked to identify our stories, we often draw a blank -- not unlike those skeptical astronomers who assumed there was nothing to see in deep space.

You have stories. You do. Of course, you have stories! If your life depended on it, you could identify at least ten of them in the next few minutes. And if I offered you a thousand dollars, you could come up with a whole lot more.

Why then, are so many of us blind to our stories? Why do so many of us insist there is nothing much to see or say?

Three reasons: First, most of us assume that a story needs to be earth-shattering in order for someone else to be interested enough to listen to it, and because most of our stories are not earth-shattering, we forget them quickly or never see them in the first place. Second, we just don't take the time. Remember, the astronomers who pointed the Hubble Telescope into deep space did it for 10 days, not 10 minutes. And third, most people don't know where to look or how to look. The "technology" we use to detect and unpack our own stories is not very sophisticated.

Consider this: If you look into the night sky with only your own two eyes, the most you are going to see, on a good night, is 3,000 stars. There is no way you will be able to detect that the universe is actually 47 billion light years wide with an estimated 100 trillion galaxies, each galaxy containing hundreds of billions stars.

You and I, my friend, are also universes. We are. Inside of each of us are 7 billion billion billion atoms. That's a one with 27 zeros after it. And while we might not have 7 billion billion billion stories inside us, we certainly have more than a few, each one capable of lighting up the night sky. And not just for our own selves, but also for the fortunate ones who get a chance to listen to them.

If you want to discover your stories (each one, by the way, encoded with its own special kind of light), you will need change the way you look for them. And, of course, before you even begin to look, just like our Hubble Telescope astronomer friends, you will need to become CURIOUS.

One way to identify your stories

Storytelling for the Revolution

Photo #1: Greg Rakozy, Unsplash

Photo #2: Jeremy Bishop, Unsplash

Posted by Mitch Ditkoff at 11:44 PM | Comments (0)

September 01, 2021SHINE!

This is Alex Romero. He shines shoes at the Denver Airport. I met him 30 minutes ago as I was making my way to Gate 54 and realizing what bad shape my shoes were in. That's when I asked him how much he charged and he told me "whatever you want to pay", which I found quite intriguing. So I took my seat, waiting for him to finish up with his other customer, and soon the shine began.

Rolling up my pant legs to my ankles, Alex asked me what it was that brought me Denver. I explained that I had flown in from Albany to attend an Intelligent Existence training, facilitated by Prem Rawat, on the subject of "noise" -- the all-too-common static in our heads -- and how we each have the ability to go beyond the noise to the place inside of us where real peace abides. Alex nodded. Then he went on to tell me that the noise in his head used to show up for him as worry, but now it has morphed into doubt.

As Alex continued shining my shoes, it seemed to me that he was some kind of shoe shine samurai. So focused he was! So dedicated! So present -- putting all of his attention into each and every stroke, each application of polish and cream, each change of cloth for each phase of the process.

"Have you ever heard of Jack Kornfeld?" he asks me. I nod. "I listen to his YouTube videos and practice the meditations he teaches. Once I experienced myself as the eye of a hawk, but got a little nervous and so I stopped."

We both laugh. Then he tells me he also gets a lot of value from the online teachings of Abraham-Hicks. I show him an Abraham-Hicks app on my IPhone. Then I ask him if his job at the airport had been affected by Covid.

"For sure," he explains. "A while back the only store open here was McDonalds. No one was flying anywhere. So I got a job as an Uber Eats driver for three months, but it was too much wear and tear on my car, so I came back to the airport."

Two days a week, Alex explains, he sets up shop in Terminal A, three days a week in Terminal B.

Then he asks me, again, to tell him the name of the man whose training I had attended a few days ago.

"Prem Rawat," I explain. "He's a really cool guy. Very accessible. Very wise and with a great sense of humor. I've been his student for 50 years."

Alex nods again, continuing to work his magic on my shoes (which, curiously, I had bought in an airport about a year ago). I look down. Wow! I have never seen them look so good. It's almost as if I can see my face in them. Astounded, I ask Alex if I he's OK with me taking his photo so I can post it on my Facebook page -- a way that friends of mine might learn about the service he provides, just in case they ever find themselves in the Denver Airport. He agrees.

As I move into position to take his photo, I notice, to my left, a small sign Alex had posted between the two chairs where his customers sit.

"Life is not measured by the number of breaths we take," the sign says, "but by the moments that take our breath away."

Posted by Mitch Ditkoff at 06:33 PM | Comments (3)